Using new technologies, scientists have discovered significant levels of lead and other toxic substances in the composer’s hair, potentially from wine or other sources. On May 7, 1824, at 7 p.m., Ludwig van Beethoven, aged 53, entered Vienna’s Theater am Kärntnertor to help conduct the world premiere of his Ninth Symphony, his final completed work. This performance, now approaching its 200th anniversary, was unforgettable in several respects.

Early in the second movement, which began with loud kettledrums, an incident highlighted Beethoven’s deafness to the audience of around 1,800. Despite the enthusiastic applause, he stood with his back to the audience, unaware of the noise, until a soloist turned him around to witness the adulation he could not hear. This was another poignant moment in a life marked by the composer’s profound humiliation due to his deafness, which had afflicted him since his twenties.

The cause of Beethoven’s deafness and other health issues, such as chronic abdominal cramps, flatulence, and diarrhea, has been the subject of debate among fans and experts. Theories range from Paget’s disease of bone to irritable bowel syndrome, syphilis, pancreatitis, diabetes, or renal papillary necrosis. However, recent findings may offer answers.

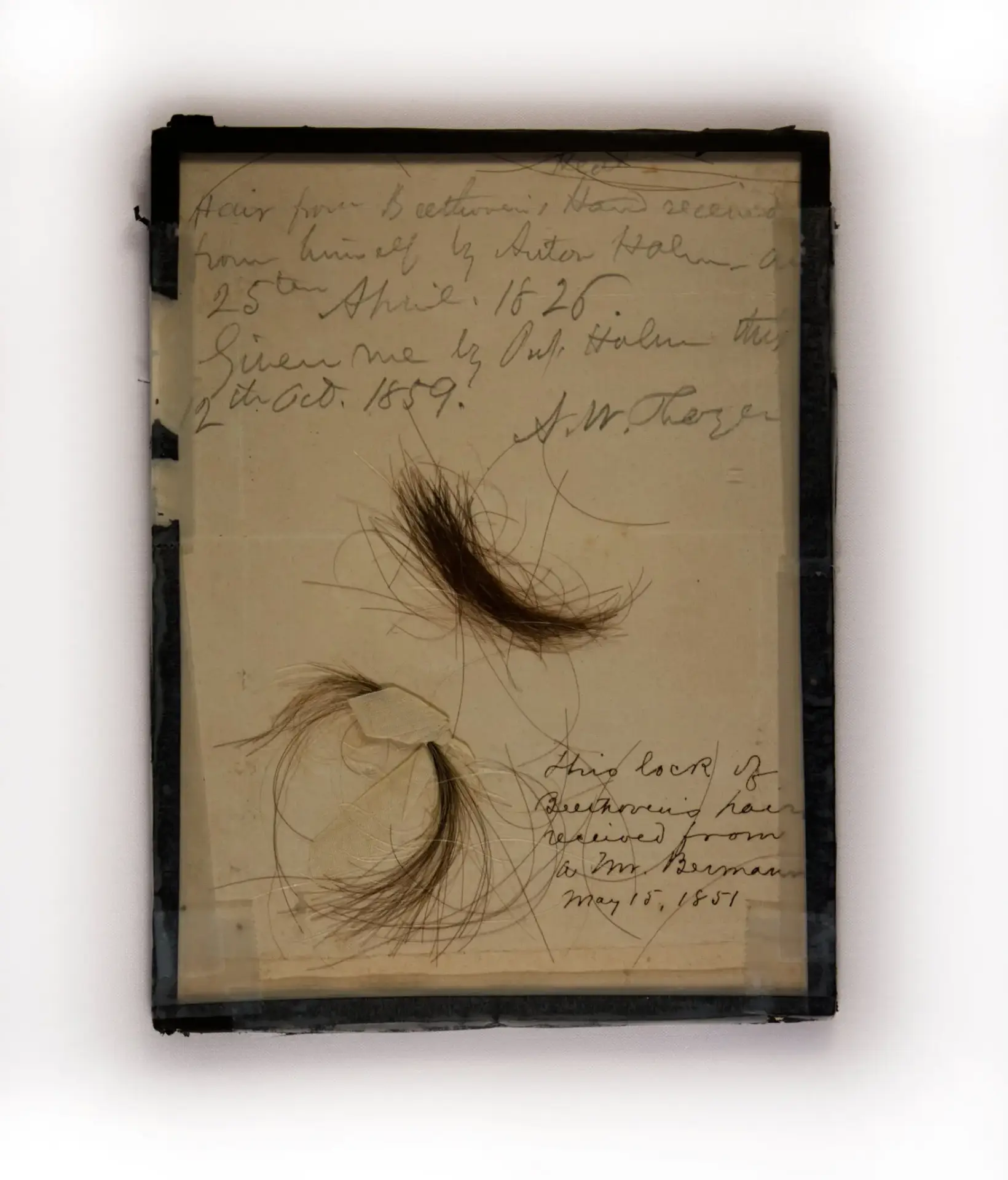

In recent years, researchers identified locks of hair, purportedly clipped from Beethoven’s head as he lay dying, as potential sources of DNA for analysis. William Meredith, the founding director of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San Jose State University, collected five such locks from auctions and museums, with three owned by Australian businessman Kevin Brown. Brown, aiming to honor Beethoven’s request for a post-mortem investigation into his illnesses, sent two locks to the Mayo Clinic for testing.

The results were startling. One lock contained 258 micrograms of lead per gram of hair, while another had 380 micrograms; normal levels are less than 4 micrograms per gram. Arsenic levels were 13 times higher than normal, and mercury levels were four times higher. These high lead levels, in particular, could explain many of Beethoven’s health problems, according to experts.

Although there is no suggestion of deliberate poisoning, lead was commonly found in 19th-century European foods, wines, medicines, and ointments. Cheap wines often contained lead acetate, known as “lead sugar,” to improve taste, while lead was also present in the corks and kettles used in winemaking. Beethoven, who consumed about a bottle of wine daily and believed in its health benefits, likely ingested significant amounts of lead throughout his life.

Beethoven’s death at age 56 in 1827 was accompanied by severe abdominal issues, with friends administering wine to him until his final moments. His last recorded words, as he received 12 bottles of wine on his deathbed, were “Pity, pity — too late!”

Despite his deafness and health struggles, Beethoven’s artistry endured. His Ninth Symphony, with its famous “Ode to Joy,” was a culmination of his lifelong pursuit of artistic expression and a testament to his enduring legacy in music.